Supreme Leader of Iran

| Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran |

|

|---|---|

Emblem of Islamic Republic of Iran |

|

| Residence | Beit Rahbari, Tehran, Iran |

| Appointer | Assembly of Experts |

| Inaugural holder | Ruhollah Khomeini |

| Formation | 3 December 1979 |

| Website | leader.ir/langs/en/ |

| Iran |

This article is part of the series: |

|

|

|

Constitution

Leadership

Executive

Legislative

Judicial

Elections

Political Parties

Foreign Policy

|

|

Other countries · Atlas |

The Supreme Leader of Iran (Persian: رهبر معظم انقلاب, Rahbare Mo'azzame Enqelab,[1] lit. Leader of the Revolution, or مقام رهبری, Maghame Rahbari,[2] lit. Leadership Authority) is the highest ranking political and religious authority in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The post was established by the constitution in accordance with the concept of Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists.[3] The title "Supreme" Leader (Persian: رهبر معظم, Rahbare Moazzam) is often used as a sign of respect; however, this terminology is not found in the constitution of Iran, which simply referred to the "Leader" (rahbar).

More powerful than the President of Iran, the Leader appoints the heads of many powerful posts - the commanders of the armed forces, the director of the national radio and television network, the heads of the major religious foundations, the prayer leaders in city mosques, and the members of national security councils dealing with defence and foreign affairs. He also appoints the chief judge, the chief prosecutor, special tribunals and, with the help of the chief judge, the 12 jurists of the Guardian Council – the powerful body that decides both what bills may become law and who may run for president or parliament.[4]

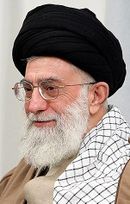

The Islamic Republic has had two Supreme Leaders in its history: Ruhollah Khomeini, who held the position from 1979 until his death in 1989; and Ali Khamenei, who has held the position since succeeding Khomeini in 1989.

Mandate and status

The Supreme Leader is elected by the Assembly of Experts, which is also in charge of overseeing the armed forces (Army, Revolutionary Guards, Police), and control of state broadcast and others (see below). The head of the Judicial branch (in Persian: قوه قضائیه) is also directly appointed by him.

The President of Iran, who is elected by universal suffrage, is the Executive President (Head of government). In 1989, the Prime Minister of Iran's office was merged with the President's office to form the current post of President of Iran. However, certain executive powers, such as command of the armed forces and declaration of war and peace, remain in the hands of the Supreme Leader.[5] Furthermore the Supreme Leader can even dismiss the president and prevent the legitimation of any law (appointed by assembly) by the institutions under his control, the Guardian Council and the Expediency Council.

Incorporation of Supreme Leader into the Iranian Constitution

The newly designed position of Supreme Leader needed boundaries which were established through the vague understandings of Khomeini’s book ‘Islamic Government’ (Hukumat-e Islami). A referendum was held in March, a month after Khomeini’s return from exile, which asked whether an Islamic Republic should be established in Iran. The masses voted strongly for an Islamic Republic and many pushed for “the people’s sovereignty to be replaced by the absolute sovereignty of God, and that Khomeini’s concept of the ‘government of the legal scholar’ (Vilayat-e Faqih) be made the principle of the constitution.” (Halm,119) Following this landslide victory Khomeini, the constitution of Iran of 1906 was declared invalid and a new constitution for an Islamic state was created and ratified by referendum during the first week of December in 1979. The new constitution consisted primarily of the ideas Khomeini presented in his work ‘Islamic Government’.

It was in the Constitution that gave the Supreme Leader a lot of power. Article 4 of the new constitution stated that “all civil, criminal, financial, economic, administrative, cultural, military, political, and all other statutes and regulations (must) be keeping with Islamic measures;…the Islamic legal scholars of the watch council (shura yi nigahban) will keep watch over this.” It is made very clear that the new form of government defined by the constitution will involve the clergy in every level. Furthermore, Article 5 solidifies the position of Supreme Leader where it states “during the absence of the removed twelfth Imam – may God hasten his return! – government and leadership of the community in the Islamic Republic of Iran belong to the rightful God fearing… legal scholar (Faqih) who is recognized and acknowledged as the Islamic leader by the majority of the population.” Article 107 in the constitution mentions Ayatollah Khomeini by name and praises him as the most learned and talented leader for emulation (marja-i taqlid). Khomeini’s consolidated as much power as possible within the government. The clergy was also involved in the government and overlooked the affairs of many governmental branches on a daily basis. The responsibilities of the Supreme Leader are vaguely stated into the constitution thus any ‘violation’ by the Supreme Leader would be dismissed almost immediately. As the rest of the clergy governed affairs on a daily basis, the Supreme Leader is capable of mandating a new decision as per the concept of Vilayat-e Faqih. (Halm, 120-121)

Guardianship of the Jurist (vilayat-e faqih)

The constitution of Iran combines concepts of both democracy and theocracy, theocracy in the form of Khomeini's concept of vilayat-e faqih. According to Khomeini, allegiance, in absence of the twelfth Imam, had to be given to the current vilayat-e faqih. Observers of the Shiite faith select the faqih by method of emulation (taqlid) of the jurist. In this new system, the jurist now oversees all governmental affairs. The “congregation rather than the hierarchy decided how prominent the ayatollah was” thus allowing the public to possibly limit the influence of the Faqih.[6] The complete control exercised by the Faqih was not to be limited to the Iranian Revolution. According to Seyyed Vali Nasr, Khomeini intended the Iranian Revolution to be the first step to a much larger Islamic revolution.

Khomeini appealed to the masses, during the pre-1979 period, by referring to them as the oppressed and with charisma and political ability was tremendously successful. He became a very popular role model for Shiites and also had some appeal to the much larger Sunni population. The Faqih should be able to have a stronghold on the Shiite population and guide them even at a global level. The striking power of the Faqih was compared to Lenin and Trotsky’s image of “Russia as the springboard country of what was meant to be a global communist revolution.” [7]

Challenges to Supreme Leader

From the reemergence of the old ideology of vilayat-e faqih, many clerics have criticized both Khomeini and his successor Khamenei for two reasons. Firstly, the position of Supreme Leader has been criticized for its active participation in daily political affairs. This contrasts greatly with the quietist views held by the renowned Grand Ayatollah al-Khoei of Iraq, his successor Grand Ayatollah Sistani, and by the well respected Ayatollah Haeri Yazdi – Khomeini’s teacher. Second, the powers held by the Supreme Leader and participation in all aspects of life by a scholar should have been a position solely for the Twelfth Imam. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had to make clear after his election that the country needs to work to hasten the return of the real leader of Iran – the Twelfth Imam. (Nasr, 133) Khoei’s appreciation for the quietist way of life removed him from being the kind of leader Khomeini became but he still had devout followers who made pilgrimage to Najaf or lived in Iraq.

Khoei was not the only one to challenge the Supreme Leader. Ayatollah Rafsanjani, recognized for his liberal attitude and President of Iran in the 1990s, withdrew funding from the ulema and factions such as Lebanon’s Hezbollah to improve the economic conditions of Iran. Khamenei recognized Rafsanjani’s challenge to the ulema but also realized the desperate economic issue in Iran. (Esposito, 211) The biggest challenge to both Khomeini and Khamenei, however, was Ayatollah Montazeri. Montazeri was placed under house arrest even though he was Khomeini’s right hand man during the Iranian Revolution. In the early years of the revolution, Montazeri gained much approval to be the next Supreme Leader but was forced to resign due to the concern he raised about number of human rights violations in Iran. (Esposito, 211) In essence, both Rafsanjani and Montazeri alluded that by having complete control over all the affairs of the country, the Supreme leader should be held accountable for all the flaws whether political, economical, or social, a feat that could only be accomplished only by the Imams.

Functions and duties of the Supreme Leader

- Delineation of the general policies of the Islamic Republic of Iran after consultation with the Nation's Expediency Discernment Council.

- Supervision over the proper execution of the general policies of the systems.

- Issuing decrees for national referendums.

- Assuming supreme command of the armed forces.

- Declaration of war and peace, and the mobilization of the armed forces.

- Appointment, dismissal, and acceptance of resignation of:

- the fuqaha' on the Guardian Council.

- the supreme judicial authority of the country.

- the head of the radio and television network of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- the chief of the joint staff.

- the chief commander of the armed forces of the country

- the supreme commanders of the armed forces.

- Resolving differences between the three wings of the armed forces and regulation of their relations.

- Resolving the problems, which cannot be solved by conventional methods, through the Nation's Expediency Council.

- Signing the decree formalizing the elections in Iran for the President of the Republic by the people.

- Dismissal of the President of the Republic, with due regard for the interests of the country, after the Supreme Court holds him guilty of the violation of his constitutional duties, or after a vote of the Islamic Consultative Assembly (Parliament) testifying to his incompetence on the basis of Article 89 of the Constitution.

- Pardoning or reducing the sentences of convicts, within the framework of Islamic criteria, on a recommendation (to that effect) from the head of the Judiciary. The Leader may delegate part of his duties and powers to another person.

List of Supreme Leaders of the Islamic Republic of Iran (1979-Present)

| Name | Picture | Born-Died | Took office | Left office | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Ruhollah Mousavi Khomeini |  |

1902–1989 | 3 December 1979 | 3 June 1989 | None |

| Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Hoseyni Khamenei |  |

1939 - | 4 June 1989 | Incumbent | Combatant Clergy Association |